Get The Visibility Your Company Needs

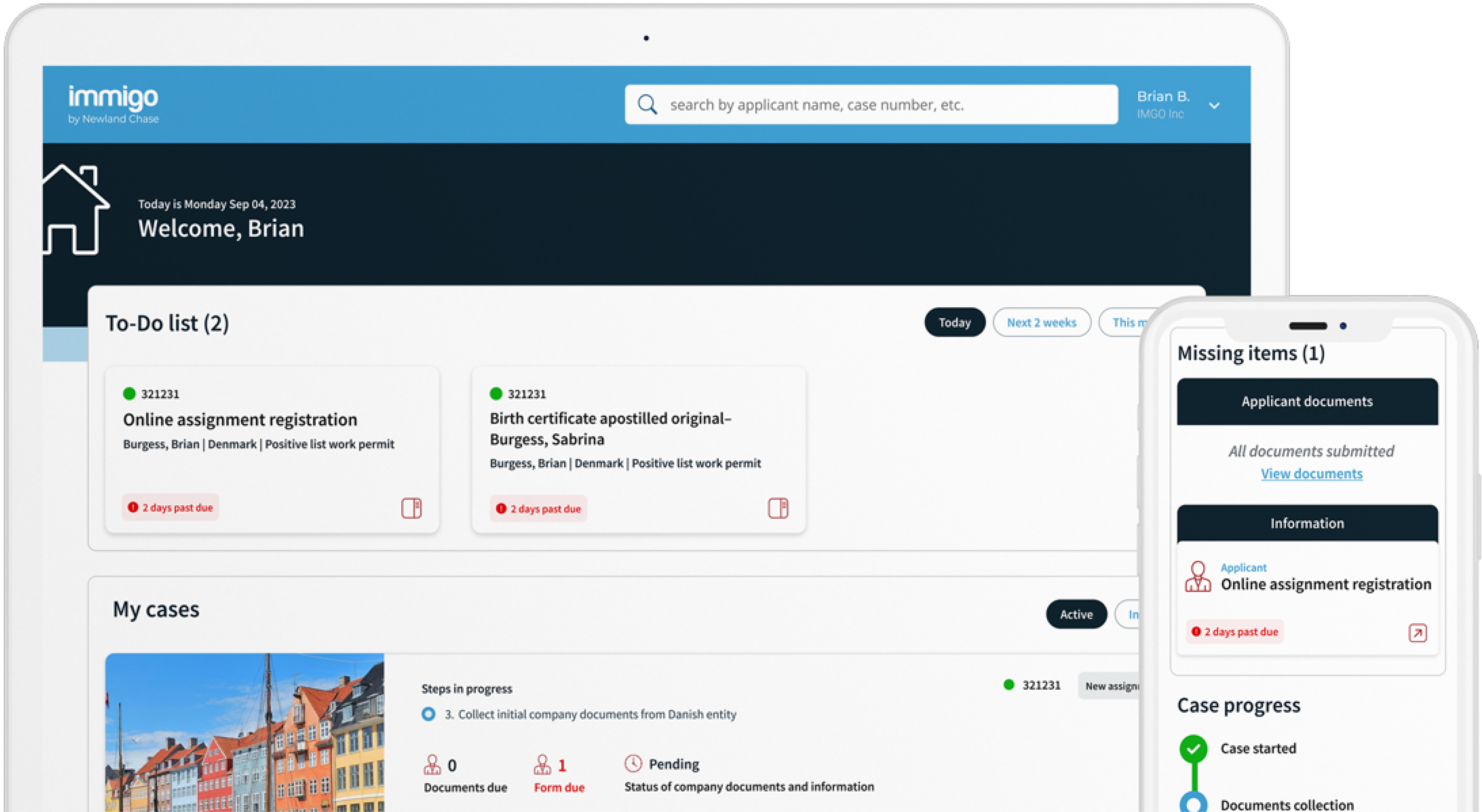

Reduce compliance risks and mobility costs while managing individual and project-related travel with ImmiSMART: the solution that unifies your travel and mobility programs.

On-Demand Webinar | Embracing the Nomad Visa Wave | APAC

Explore the changing remote work dynamics in the APAC region as our expert panellists offer insights on the newly introduced digital nomad visas in South Korea, Japan and Indonesia. Join us to uncover the advantages and eligibility criteria associated with these new visas to gain invaluable knowledge on how to utilise these effectively for talent attraction and retention.